>

With the rebellion crushed in Bohemian and the Austrias, the Rebel cause fled, taking with it their ideas and belligerent spirit. Protestants throughout Europe were wary of entering a general, large scale war. Many nations were already involved with their own internal and external conflicts. France had recently been involved in no less than nine civil wars, all centered upon religious strife between the Calvinist Huguenots and the Catholics. England was also trying to find stability post Henry VIII, as the religion question was also taking center stage. Sweden was involved in eastern wars, which kept their future involvement at bay. Many of the German electors had agreed under the Protestant Union meetings in 1621 not to carry on the conflict. An armistice was signed in April 1621 at Mainz. Frederick and his kingdom was forced into a cease-fire, and it was expected that Frederick would renounce his claim to the Bohemian throne. He refused, hoping rather to keep or take back his land by war rather than diplomacy. This refusal instigated Bohemia’s demise. Frederick’s appointed general, Mansfeld was, as previously illustrated beaten by the Catholic powerhouse Count Tilly and the Spanish General Spinola. Upon fleeing the Empire, and being beaten often, Frederick and Mansfeld found support from the Danish King Christian IV, also elector of Brunswick and Holstein.

Christian was one of Europe’s most powerful men at the War’s outset. He was rich through trade, diplomatically stable, and militarily powerful. His entrance into the War on the Protestant side, should have proved a major boon, instead, Christian’s entrance was a comedy of errors. Christian began helping both Frederick and Mansfeld, who were now both outlaws of the Holy Roman Empire. Because of Tilly’s overwhelming success against the Protestants, European diplomacy was now experiencing a dramatic shift, which should also have been a cause for Protestant optimism in spite of the pessimistic reality. Protestants were alarmed due to the extreme northwestern occupation held by Count Tilly’s armies. The Netherlands was concerned, because Habsburg forces surrounded her borders. England, began to support the Dutch with aid against what seemed to be a certain Spanish venture to retake the “heretic” Dutch. France, always wary of the Habsburg family, started to take steps leading toward Protestant support, in spite of the staunchly Catholic, Protestant murderer Marie de Medicis involvement. Marie and her mother Catherine orchestrated much bloodshed and turmoil in France, as Huguenots battled Catholics for decades. King Henry IV died leaving his young son, and Marie, to rule France. Henry was a notorious vacillator between religious positions, but his death plunged France into internal strife. It was not until Cardinal Richelieu was appointed in 1624, that France’s diplomatic ship was righted. Though Catholic, Richelieu was concerned with the growing Habsburg dominance. He openly began opposing the Holy Roman Empire and Spain. With these concerns in mind, Christian of Denmark seemed ultimately destined for success.

Mansfeld was given money and support to raise a new army in 1624, but that army was never fully realized. Spain invaded The Netherlands at Breda, and new forces were demanded to beat back the Spanish venture. France, who was supporting the Dutch at Breda, oddly, would not allow Mansfeld’s army to pass into The Netherlands. The Dutch, also, would not let the army land by sea. Over time, the newly raised army died of disease or starvation, with the remaining soldiers entering Breda, as it fell to the Spanish. This blunder was an ill omen to future failures. England then began to organize a Scandinavian Alliance with Christian IV, Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden, and Georg-Willem of Brandenburg. This “Grand Alliance” was preposterous, because for one, Christian and Gustavus Adolphus were recently involved in a war of their own, and also Georg-Willem could not trust the Scandinavians, because of their stated goal to create an empire in northern Germany. Gustavus demanded opulent terms for his entrance against the Catholics, Christian’s terms were less grandiose, so England appointed Christian as the new Protestant leader. Georg-Willem simply was not interested with England’s scheme. Christian was now given complete control of the Protestant cause, and free reign to involve himself in the Holy Roman Empire’s politics.

Christian’s claims in the north caused resentment and hatred amongst the other electors, who viewed Christian as an upstart. In spite of this, Christian and his supporters were given the Lower Saxon Circle’s approval as they elected him their director in 1625. With these newer alignments, Ferdinand appointed Albrecht Waldstein, “Wallenstein” to raise an army to succor Count Tilly. Wallenstein was not of the nobility, but he grew rich directly from plunder and pillage during the first phase of the war. He not only grew rich, but also accumulated opposition of his own. Wallenstein could be and was brutal, but his effective warring style was exactly what the Emperor desired. With a new, well trained and equipped army coming, Count Tilly received command to pass into Lower Saxony in July 1625. The Danish Phase of the War was now underway.

Tilly’s army was unstoppable as well as unbridled, leaving a massive path of destruction wherever they invaded. Wallenstein’s forces would only add to the magnitude of destruction, when he joined forces with Tilly later in 1625. Because of Tilly and Wallenstein’s overwhelming dominance, England, Denmark, and The Netherlands signed an open alliance against the Holy Roman Empire in 1625. Christian was reeling, and he needed more help desperately. England and The Netherlands, simply could not afford to supply men, so they supplied 350,000 florins a month instead. Soon enough, however, King Charles I of England would lose his money, support, and head as Civil War broke out between Protestants and Catholics on the home-front.

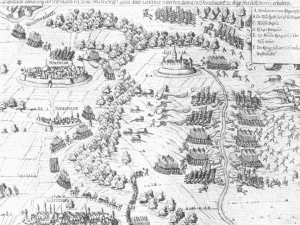

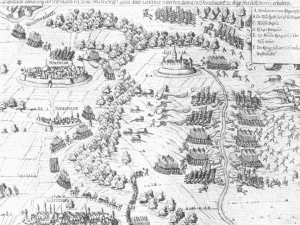

Christian then tried to break Tilly’s increasing dominance by sending two forces, one to Osnabruck, and one to Hesse-Cassel. Both were failures, and the venture within Hesse-Cassel cost Christian the life of his general, Halberstadt, who died of a fever. Further complications hindered the Protestant cause, as Mansfeld was spurning any agreement to work with the Danish. He moved across the Elbe river, and into close contact with Wallenstein’s forces, who controlled the region. At Dessau, Mansfeld wanted to occupy a bridge that would allow Wallenstein further passage into Saxony. Mansfeld proved no match for Wallenstein’s army as he reinforced it with artillery and more men. After a month of fighting, Mansfeld fled to Brandenburg, thus allowing Tilly free access northward, and further endangering Christian. Tilly completely destroyed Christian’s army at the Battle of Lutter in August 1626. Christian and Mansfeld’s armies from this point forward were struggling to stay alive. While fleeing Wallenstein, Mansfield and his successors died outside of Sarajevo, Bosnia Herzegovina. With no competent leader, Mansfield’s remaining troops left the fray.

Other events also proved equally disastrous during this time. Bethlen Gabor of Transylvania and the Ottoman Turks were both forced out of the War, leaving Christian the only remaining Protestant threat by 1627. Wallenstein turned his bloody focus toward Denmark, and undertook a campaign that made him infamous. With no real opposition in his way, Denmark had to succumb to Wallenstein who captured all of Denmark except the capital on the island of Zealand. Wallenstein needed a navy, but no one would give it to him, as many began to oppose Wallenstein and his methods. Ferdinand was forced to recall his general, who went into retirement for the time being. Denmark was brought into negotiations, which ended the Danish Phase with the Treaty of Lubeck in 1629. Ferdinand’s power almost absolute in the Empire was now arrogantly on display. He issued the Edict of Restitution also in 1629, which stated that all previously Catholic, now Lutheran lands, were to be retaken, thus annulling the Peace of Augsburg. Even Wallenstein was outraged at such a declaration, and rightly postulated that such a foolish edict would bring Sweden into a new phase of the War. Within a few months, Gustavus Adolphus lent his aid to the Lutherans, and Wallenstein would need to be recalled from his retirement.