In the mid 1880’s a Sudanese Muslim believed that Allah had chosen him to be the Mahdi, next or sent one. Upon this belief, many of the Sudanese Muslims tired of Christian British rule decided to join the Mahdi’s army. The situation became serious quickly as the Mahdi’s insurgents began attacking British outposts on their way to Khartoum, capital of Sudan and a major British stronghold. As the forces advanced, Sudan entered open rebellion, and the British Colonialists began to fear the worst. Many British detachments were defeated by the Mahdist forces due almost solely to the fact that the British were unprepared for Sudan’s climate and geography. The Mahdi led most forces on a labyrinthine goose chase that tired the Brits, and made crushing colonial defenses easy. Islam was spread to many non-Islamic areas throughout the countryside, most notably, Darfur. Once regions were Islamized, the Mahdi began to “cleanse” the regions with Sharia law, killing many more defenseless “infidels” according to the Koran and Allah’s direction.

Britain decided that this was not a fight they wanted to continue, and sent General Charles Gordon with evacuation orders in 1884. Upon his arrival, and wonderful standing amongst the Sudanese, Gordon began evacuating many. As evacuations were being carried out, Gordon decided that it was too late for him to leave. In the best interest of the remaining British and Sudanese in Khartoum, he would defend against the Mahdi. Gordon created an extensive landmine network as well as rerouted the Nile around Khartoum as an extra defensive barrier. This plan worked for many months until the Nile’s flood waters assuaged, and the Mahdi’s forces finally found enough courage to traverse the mine fields. Khartoum was by this point starving, having been surrounded and cut off by the Mahdi. The British disinterest in the area also left Gordon and Khartoum on their own island in the Muslim ocean to die. January 28-30, 1885 Khartoum was laid siege, and fell. Gordon was beheaded according to Muslim Law dealing with infidels. His head was wrapped and brought to the Mahdi, who hung it in a tree for all to look at in shame. A few months after this battle; however, the Mahdi himself suddenly died.

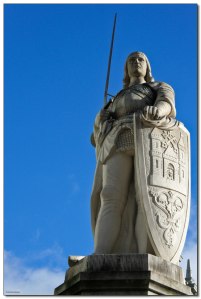

It would be many years later when the British finally decided that Sudan was too strategic to not have as part of the growing British Empire. Plans were drawn to recapture what the Mahdi and his successors had taken. Britain sent General Kitchener with his orders to retake Khartoum and the rest of Sudan. He arrived from Egypt in 1886 with some success, but it was not until September 1898 that Kitchener scored a major victory in Sudan.

At 6 AM, Kitchener’s mixed British, Egyptian, and Sudanese force totaling 25,000 men met the successor Mahdi’s 52,000 troops. From the outset, it was apparent that British technology was superior. The Mahdists attempted an ill-fated charge into British Maxim guns, and lost 4,000 immediately. Another Mahdist charge was repulsed before Kitchener began his offensive. He separated his army into columns with the 21st Lancers in front to clear the plains of Omdurman outside of Khartoum. 400 Lancers soon found themselves fighting 2,500 Mahdists, but the British were valiantly victorious (three Victoria’s Crosses were awarded from this skirmish).

Kitchener had to continuously re-establish his army’s form, as the Madhists made many frontal charges against his lines. Each line was reinforced. Maxim guns and artillery proved too much for the enemy forces, and they broke by 1130 AM. Kitchener moved forward and took both Omdurman and Khartoum.

The defeated Mahdidsts lost app. 9,700 dead, 13,000 wounded, and 5,000 prisoners of war. Kitchener’s army lost 47 dead and 340 wounded. The war for Sudan was finally ended in 1899 after the Battle of Umm Diwaykarat, with Britain’s overlordship restored.

Kitchener became a hero and went on to many political and military victories after Omdurman, yet there was someone who made a larger name for himself from this battle, Sir Winston Churchill. His book, The River War: An Account of the Reconquest of the Soudan, not only detailed what took place in Sudan, but also launched a political career that touched the world during the next half-century.